Flattening an infill plane

This is probably about one of the most difficult areas in the making of a dovetailed infill plane.

The amount of forces and stresses generated from the peining usually causes the whole structure to convex depending on the force of the peining. The longer the plane body the greater the amount of movement at the centre of the plane. Flushing the dovetails off after the peining will not straighten the plane out. The only way to flatten the sole is with a milling machine, rubbing the sole of a plane on an abrasive surface is not going to work. However most planes will still work if they are not entirely flat, but this isn’t that kind of tool.

After peining, the amount of removal necessary to bring about a flat surface would be far too much for filing or abrading. The abrading system practised by quite a lot of people would only level off the high spots. The pressure applied to the plane to do this will flex the body of the plane to try and match the surface you are pushing against only to spring back once you release it. This usually means that you will still have a plane with a camber or a twist.

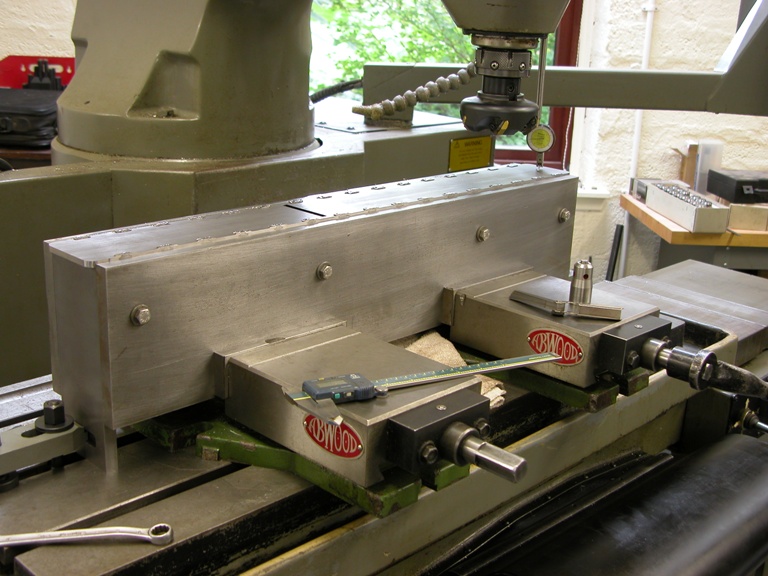

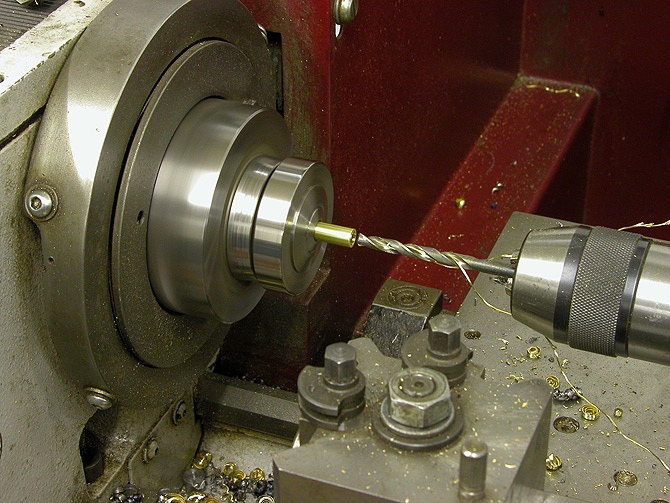

The body of a plane can be very difficult for work holding. It would be very expensive to make a jig for this purpose, so for the small number of planes that I make I have chosen to improvise as shown on the above picture. This shows one side open so that the plane can be seen.

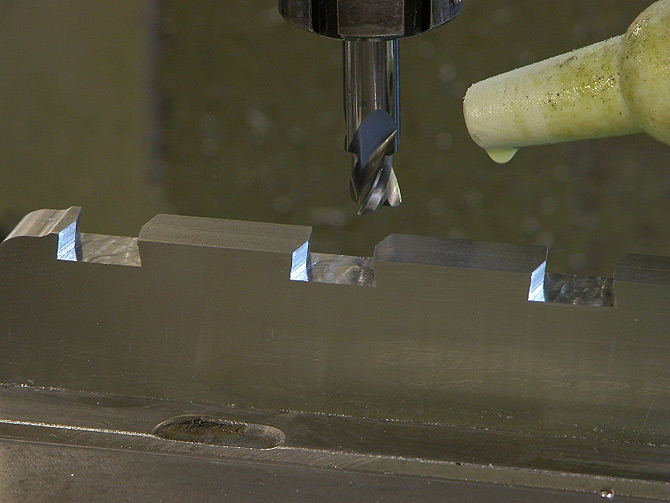

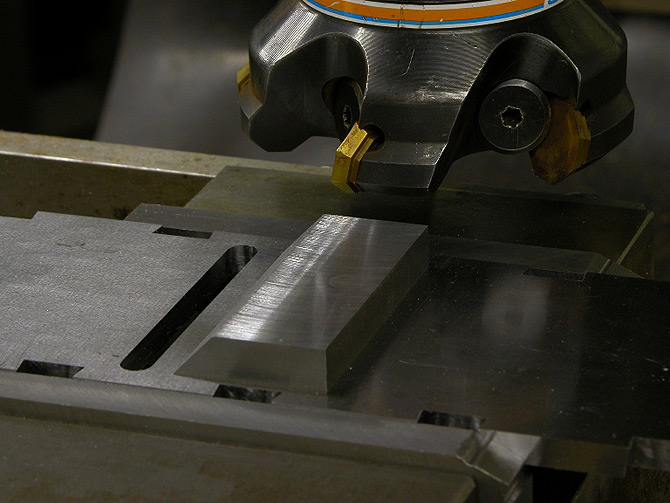

At this stage the dovetailing on the sides will only have been partly flushed so that they will stand a little bit proud and I only clamp along this narrow line. There is no contact on the sides but just along the bottom line i.e. dovetail line. The reason for clamping along this narrow line, assuming that there is the usual slight twist, is it will clamp the plane body without changing its shape within reason and this will then allow any twist or deformations to be removed. If I was to clamp directly on to the sides of the plane then I would only change the shape of the plane which would spring back the moment it was released from its work holding jig. Of course the removal of this excess material is done with a very fine cut and the correct tool, no heat must be generated whatsoever.

Although time consuming this system does work and I can achieve some tight tolerances of +/- .0015. This is only a way of removing the excessive material. The rest of the flattening process is another story.

There is no way at any stage I could use a surface grinder on an infill plane as this type of plane is a thin walled box section and as grinding generates heat the structure would be compromised. This would make the whole process impossible.

This is my holding jig shown with the last clamping plate in position.

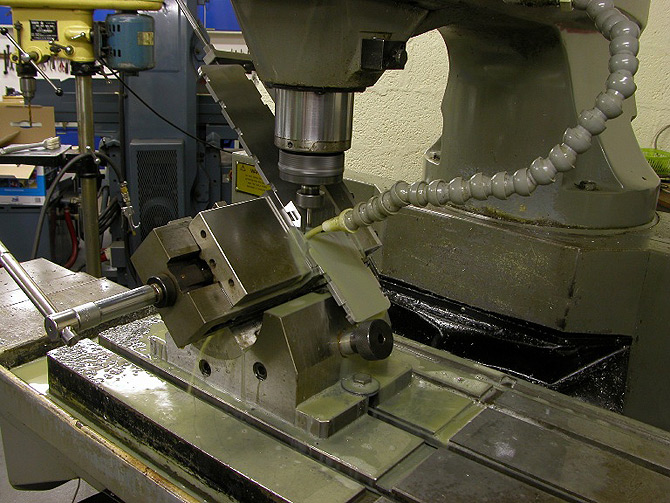

A picture showing the main parts of an A1 28 ½” jointer but with a long way to go.